RRR.RRRR.

Stuck keyboard? Railroad Pirates? Not really. Rather, first, the Regional Rail Reorganization Act of 1974, the “3-R Act{1}, ” and second, the Railroad Revitalization and Regulatory Reform Act of 1976, the “ 4-R Act{2}” -- two acts of Congress that in the 1970s began an era of restructuring and reduced regulation of railroads that significantly changed their financial health and competitiveness.

The history and financial success of North American railroads has endured several boom & bust cycles since rails were first laid by the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad in 1827. While trucks existed prior World War II, it wasn’t until the rapid growth of the Interstate system in the 1950s that trucks had the range and efficiency to compete with rail in the business of long-distance freight service. Government subsidization of trucks and barges in the 1950s and 1960s fueled competition from trucks while at the same time rigid government oversight prevented railroads from making necessary and commonsense changes to pricing and services to compete with the emerging truck competition leading to a railroad financial crisis by 1970. Most, if not all, of us began our railroad careers in this post 1970 railroad crisis so it is helpful to understand the history and legislation that led to the revitalization and reduced regulation of the rail industry.

The two largest railroads the Northeast U.S. in the early twentieth century were the New York Central and Pennsylvania Railroads, and who happened to be two of the first victims of the rail industry financial crisis. Historically fierce competitors, the two railroads hoped by merging to save as much as $150 million a year in operating costs and eliminate hundreds of miles of side-by-side track. On May 8, 1962 the stockholders of the two railroads approved the merger of their operations but it took another four years for the Interstate Commerce to approve the merger after imposing several conditions. On February 1, 1968 the railroads finally combined as the Penn Central Co. but the future of the new company was not to be happy or profitable. On June 21, 1970 the Penn Central filed a petition for reorganization under § 77 of the Bankruptcy Act{3} followed shortly thereafter by bankruptcy petitions of seven more railroads{4}.

In response to the rail crisis in the northeast U.S., Congress supplemented § 77 of the Bankruptcy Act with the 3-R Act (Regional Rail Reorganization Act of 1973)1 resulting in the creation of the Consolidated Rail Corporation, better-known as “Conrail,” and the United States Railway Association{5} and provided funding that authorized the issuance of up to $15 billion in federally guaranteed obligations and $500 million in direct Federal payments for interim cash assistance to bankrupt railroads{6,7}.

In 1976 Congress followed up the 3-R Act with the 4-R Act (Railroad Revitalization and Regulatory Reform Act of 1976).2 While the 3-R Act was primarily concerned with the rail crisis in the Northeast U.S., the 4-R Act encompassed measures to restore the health of the nation’s private railroad system in a number of ways. It allowed railroads flexibility in setting rates and the freedom to set rates for traffic where there was competition; provided a framework for reform of the Interstate Commerce Commission; contained provisions for rehabilitation and improvement funding; provided a framework for implementation of northeast passenger transportation corridor and the creation of the National Railroad Passenger Corporation, better known as “Amtrak;” revision of rules for line abandonment and discontinuous of lines; and, most importantly, removed many unnecessary regulatory restrictions which had hindered the ability of railroads to operate efficiently and competitively{8}.

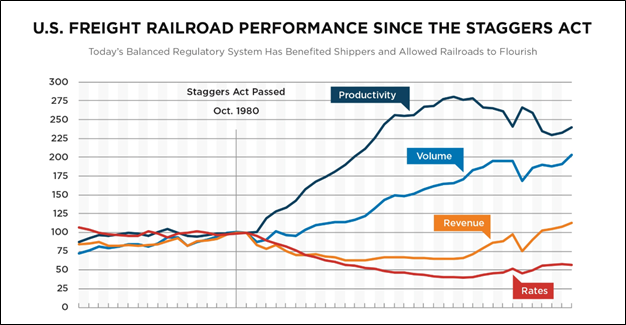

The 3-R and 4-R Acts were followed by the Staggers Rail Act of 1980{9}. In the 30-year period preceding 1980, railroad market share had declined by 33 percent. Post Staggers, market share increased to over 40 percent and return on investment increased from 2 percent in the 1970s to nearly 8 percent by 2009.

Source: Association of American Railroads

Many provisions of the 3-R, 4-R and Staggers Rail Act have been superseded or amended by sequent legislation and the railroad companies and rail lines that the 3-R Act sought to preserve have been absorbed by present-day operators. Present-day case references to the 3-R Act frequently involve the disposition of property{10} and FELA{11} litigation that relate back to the division of assets or liabilities under the act. The Staggers Rail Act, being broader and more recent that the 3-R and 4-R acts, is frequently litigated in respect to rate regulation and abandonments, among other issues. The portions of the 4-R act that dealt with financing for railroad restoration were superseded by acts such as the Transportation Equity Act for the 21st Century (TEA-21) (1998-2003), the Transportation Investment Generating Economic Recovery, or TIGER I and TIGER II, discretionary Grant programs (2012), the Railroad Rehabilitation and Improvement Financing Program (2013), and the present-day Consolidated Rail Infrastructure and Safety Improvements (CRISI) Program{12}. Remaining or unimplemented provisions of the 4-R Act addressing reform of the Interstate Commerce Commission were superseded by the ICC Termination Act of 1995{13}.

One enduring provision of the 4-R Act addresses taxation of railroads. To address Congress’ conclusion that railroads were easy prey for State and local tax assessors in that they did not vote and could not easily remove themselves from the locality{14), Article III, Sec. 306 of the 4-R Act stated that it would be unlawful for a State, or a political subdivision of a State to levy assessments or taxes at rates higher than true market value of the rail transportation property or than the ration assessed for other commercial and industrial property{15}. A tax discriminates under the 4-R Act when it treats groups that are similarly situated differently without sufficient justification for the difference in treatment{16}. The 4-R Act further provided Railroads may invoke its remedies only when tax discrimination exceeded five percent, compared to similar commercial or industrial property, and only in respect to that portion of the tax exceeding said threshold{17}. As State and local authorities seek to fund public projects and budgets, Railroads continue to face discriminatory taxation.

Current railroad tax disputes often center upon whether an assessment is a “tax” or a “fee.” The distinction between a tax actionable under the 4-R Act and a fee depends upon how the funds are used{18}. A government levy is a tax if it raises revenue to spend for the general public welfare, whereas if the charges are tied to a particular benefit obtained by a specific taxpayer, it is a fee and non-actionable under the 4-R Act{19}. Railroads have successfully argued that taxes that include the value of intangible property{20} or where caps of tax increases are available to most commercial property but not railroads{21} violate the 4-R Act. Whether utility and storm water fees are in violation of the 4-R are fact dependent. The town of Cicero, Illinois’ motion to dismiss claims by BNSF that sewer charges by the town violated the 4-R Act was denied where rate changes that only applied to railroads increased BNSF’s monthly charge from $6,643 to $90,300{22}, but the imposition of a $416,748 stormwater charge against Norfolk Southern by the City of Roanoke, Virginia was held to be a fee, not a tax, and therefore not in violation of the 4-R Act{23}.

The efforts to reduce regulation of the railroad industry that began in the 1970s is remarkable in that it was result of efforts under bipartisan administrations beginning in 1973 with the enactment of 3-R Act by President Richard M. Nixon, and then augmented by the 4-R Act signed into law by President Gerald R. Ford in 1976, broadened by the Staggers Rail Act signed into law by President Jimmy Carter in 1980 and the I.C.C. Termination signed by Bill Clinton in 1995. The combination of the 3-R, 4-R, Staggers Rail and ICC termination Acts have had a significant impact to the health of the nations railroads and continue to be relevant today.

References

- Pub. L. No. 93-236, 45 U.S.C. § 701 et seq.

- Pub. L. No. 94-210, 45 U.S.C. § 801 et seq.

- 11 U.S.C. § 205

- Blanchette v. Connecticut General Insurance, et al, 419 U.S. 102 (1974), at 102. The seven additional railroads were the Reading Co, Erie Lackawanna Railroad Co., Central Railroad Co. of New Jersey, Lehigh Valley Railroad Co., Boston & Maine Corp., Ann Arbor Railroad Co., and the Lehigh & Hudson River Railroad Co.

- The United States Railway Association was a governmental corporation overseeing the operation of Conrail and operate other bankrupt and failing freight railroads and was in operations until 1986.

- President Richard M. Nixon Statement on Signing the Regional Rail Reorganization Act of 1973. January 2, 1974, https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/documents/statement-signing-the-regional-rail-reorganization-act-1973

- Note that in 1997, Norfolk Southern Corporation and CSX Corporation agreed to acquire Conrail through a joint stock purchase whereby they split most of Conrail’s assets between them and restructured remaining Conrail operations into a jointly-owned Switching and Terminal Railroad.

- President Gerald R. Ford Statement on the Railroad Revitalization and Regulatory Reform Act of 1976, February 5, 1976, https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/documents/statement-the-railroad-revitalization-and-regulatory-reform-act-1976

- Pub. L. No. 96-448, 49 U.S.C. § 10101

- In example; National Railroad Passenger Corporation v. Southeastern Pennsylvania Transportation Authority, 56 F.4th 129 (D.C. Cir., 2022) interpreting the impact of US Railway Association Final System Map; and Matter of Central RR.Co. of New Jersey, 473 F. Supp 225 (D.N.J., 1979)

- Federal Employers’ Liability Act (“FELA”), 45 U.S.C. §§ 51-60.

- The Consolidated Rail Infrastructure and Safety Improvements (CRISI) Program is authorized under 49 U.S.C. § 22907..

- Pub. L. No. 104-88, 49 U.S.C. § 10501 et seq

- Union Pac. R.R. Co. v. Wis. Dep’t of Revenue, 940 F.3d 336 at 339 (7th Cir. 2019)

- 49 U.S.C. § 11501

- BNSF Ry. Co. v. Town of Cicero, 592 F, Supp. 716 at 730, (N.D. Ill. 2022), citing Ala. Dep’t of Revenue v. CSX Transp., Inc., 575 U.S. 21, at 26 (2015)

- CSX Transportation, Inc. v. New York State office of Real Property Services, 306 F,.3d 87 at 97, (2nd Cir., 2002)

- BNSF Ry. Co. v. Town of Cicero, at 730

- Id.

- See BNSF Ry. Co. v. Or. Dep’t of Revenue, 965 F.3d 681, (9th Cir., 2020), and Union Pac. RR. Co. v. Wis. Dep’t of Revenue, 940 F.,3d 336, (7th Cir. 2019.)

- See CSX Transp. Inc. v. S.C. Dep’t of Revenue, 959 F.3d 622, (4th Cir., 2020)

- BNSF Ry. Co. v. Town of Cicero

- Norfolk S. Ry. Co. v. City of Roanoke, 916 F.3d 315, (4th Cir., 2019)